Hip-Hop explodes onto the scene with energetic breakdancing crews, rhythmic beats, and lyrics that pack a punch. But this culture boasts a rich and complex history, deeply rooted in the Bronx, New York. Here, African American communities used artistic expression to celebrate their identity and confront social struggles. Today, we kick off our exploration of hip-hop’s roots, tracing its journey from early influences to the powerful voice it has become.

Before the Rhymes: The Seeds of Hip-Hop

African-American communities in the US nurtured cultural expressions that became the foundation for Hip-Hop, laying the groundwork for a powerful movement that would later dominate the airwaves:

-

- West African Griot Traditions: Griots, skilled travelling West African musicians and oral historians, captivated audiences with rhythmic storytelling and improvisation. Their art form bears an uncanny resemblance to rap, where artists weave narratives and social commentary into their verses..

-

- The Blues: Born from the depths of hardship and resilience during the era of slavery, the Blues is a melancholic genre that laid bare the struggles and aspirations of black communities. The soulful vocals and poignant storytelling of blues artists continue to influence hip-hop’s expressive nature.

-

- DJ Culture: DJs like Kool Herc became pioneers by not just playing records. They were weaving magic, creating extended instrumental breaks (known as “beats”) through techniques like scratching. This innovation provided the rhythmic canvas upon which rappers would paint their lyrical masterpieces, becoming a cornerstone of hip-hop music production.

The Pioneering DJs and Crews

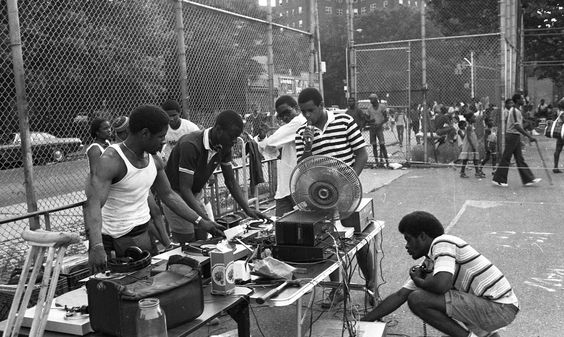

The 1970s witnessed the rise of legendary DJs who laid the foundation for Hip-Hop music production. Kool Herc, with his innovative use of turntables and breakbeats, is widely considered the “founding father” of Hip-Hop [7]. Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five pushed the boundaries further, incorporating innovative techniques like scratching and beat juggling into their performances [8]. Afrika Bambaataa, a DJ and community leader, formed the Zulu Nation, a crew that promoted peace, unity, love, and having fun (P.U.L.L.H. philosophy) through Hip-Hop culture [9]. These pioneers not only entertained crowds but also fostered a sense of community and belonging for young people in the Bronx.

The Birthplace of Hip-Hop: A Cultural Oasis in a Concrete Jungle

Imagine this: Block parties pulsating with rhythms, DJs weaving magic with turntables, and young voices spitting rhymes that painted vivid pictures of their reality. This wasn’t a scene from a movie; it was the lifeblood of the Bronx in the 1970s. In these concrete jungles, amidst economic hardship and social unrest, a cultural movement emerged. DJ Kool Herc became the architects of a new sound. They extended instrumental breaks in popular songs, creating the canvas for a new art form – RAP. Afrika Bambaataa, a DJ and community leader who saw the potential of this nascent movement, promoted unity and creativity through his crew Zulu Nation, using Hip-Hop as a tool for social empowerment [10].

Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five: Tech wizards and lyrical storytellers

These Bronx legends weren’t just playing records; they were revolutionising music production. Grandmaster Flash wasn’t just a DJ; he was a magician behind the turntables. He introduced techniques like scratching and beat juggling, adding an entirely new layer to the music [11]. The Furious Five, the rapping crew that complemented Flash’s wizardry, weren’t just dropping rhymes; they were weaving narratives. Their energy and storytelling raps like “The Message” resonated with a generation yearning for a voice. Tracks like these addressed issues of police brutality, racial discrimination, and the harsh realities of inner-city life, giving voice to a marginalised community.

Rhymes with Resistance: A Microphone as a Weapon

Early rap wasn’t just about entertainment; it was a powerful form of protest. Rappers like KRS-One, a future hip-hop legend, declared, “Rap is not R&B, this is revolution by rhyme” [12]. These artists weren’t afraid to challenge the status quo and advocate for change. Their lyrics became weapons, wielded against social injustices. Tracks like Public Enemy‘s “Fight the Power” became anthems for a generation demanding equality.

The Golden Age of Hip-Hop (1980s)

By the 1980s, Hip-Hop had transcended the borders of the Bronx, spreading its infectious energy and message of empowerment across America. This era, often referred to as the “Golden Age,” witnessed the rise of iconic artists and groups who shaped the sound and lyrical content of rap music. Here are a few key figures:

-

- Run-DMC: This groundbreaking rap trio from Queens, New York, brought a raw and aggressive sound to the genre. They stripped down beats, featuring prominent use of the drum machine, and their lyrics often focused on street life and social commentary [13].

-

- LL Cool J: A charismatic rapper from Queensbridge, brought a smoother and more radio-friendly sound to Hip-Hop. He addressed social issues like poverty and crime but also incorporated themes of love and braggadocio into his music [14].

-

- The Sugarhill Gang: This group’s 1979 song “Rapper’s Delight” is often considered the first commercially successful rap song. It brought Hip-Hop to a wider audience and paved the way for other artists to break into the mainstream [15].

-

- Public Enemy: This politically charged rap group from Long Island, New York, used their music to raise awareness about social injustice, racism, and police brutality. Their powerful lyrics and confrontational style challenged the status quo and made them one of the most influential groups in Hip-Hop history [16].

Hip-Hop’s Global Rebellion

Hip-Hop’s infectious energy transcended geographical boundaries. From breakdancing crews in Paris to graffiti artists in Tokyo, the movement resonated with diverse audiences worldwide. It wasn’t just about copying American artists; local artists began incorporating their own cultural identities and languages, creating a truly global phenomenon. Breakdancing crews like France’s Rockin’ Squatters and Senegal’s Positive Black Soul put their own spin on the movement, showcasing electrifying dance styles that reflected their cultural backgrounds. In these diverse interpretations, Hip-Hop wasn’t just music; it was a language of rebellion, a way for young people around the world to express their struggles and aspirations.

Conclusion

Hip-Hop’s journey from Bronx block parties to a global phenomenon is a testament to the power of artistic expression. It emerged as a voice for marginalised communities, a platform for confronting social issues, and a celebration of creativity. In the next part of our four part blog series, we‘ll delve deeper into the evolution of Hip-Hop, exploring the rise of Gangsta rap with N.W.A., the East Coast-West Coast feud, and the emergence of iconic figures like Dr. Dre, Tupac Shakur, The Notorious B.I.G., and Lauryn Hill and other underground artists.

Sources:

[1] “DJ.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/art/disc-jockey

[2] Rose, Tricia. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Wesleyan University Press, 1994.

[3] Chang, Jeff. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. St. Martin’s Press, 2005.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Keith Haring.” Biography.com, A&E Television Networks, 14 April 2014, https://www.haring.com/!/about-haring/bio

[7] Chang, Jeff. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. St. Martin’s Press, 2005.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] KRS-One. “Rap Is…” Criminal Minded. JVC Records, 1987.

[13] Chang, Jeff. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. St. Martin’s Press, 2005.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Rose, Tricia. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Wesleyan University Press, 1994.

[16] Ibid.

Additional Resources:

-

- The Hip-Hop Archive: https://sites.harvard.edu/hiphoparchive/

-

- National Museum of African American History & Culture: https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/initiatives/hip-hop-revolutions

-

- National Geographic: Hip-Hop’s History in 10 Tracks